Questions from Alpert Award panelists Thomas DeFrantz, Simone Forti, and Alma Guillermoprieto, Wendy Perron, editor-in-chief, Dance Magazine, and Irene Borger

Q

You are so extraordinarily charismatic; is there a pitfall in that?

Charisma is a mysterious ingredient that attracts attention to your work. It is flattering to be recognized for being charismatic or attractive, but it is important to remain grounded about these things: they just are. I seriously doubt that charisma could be an issue for a performer. Yet if the artist must be beautiful and must be charismatic to attract an audience, he, or especially she, must also be a thinker.

Q

Why especially if it is a ‘she?’ How much is ‘seduction’ part of being a performer in front of an audience?

I honestly think society is programmed to see woman as seducer (the eve syndrome) and accept male seduction as secondary. Clearly anyone who watches Bill T. Jones has to acknowledge the power of his beauty and the skill of his seduction. For me the only difference is if the SHE is a black African body, then the seduction is somewhat ‘surprising,’ because “Africa is not sexy.” How I, (the choreographer) see the world is re-presented in the space I create on stage, what I value about democracy, religion, etc. is manifest in the way I use time, space and force. A philosopher is described as creative person or someone who thinks deeply. The general misconception is that dancers simply ‘do,’ and don’t think. I am talking about the dangers of being seen only as an object, and not subject.

Q

How is that manifested?

Through complex dances that provoke dialogue or conversation. In my work I tackle themes such as dislocation, exile: these are complex matters, that hopefully should lead to deeper conversations either with audiences, fellow Africans, critics, etc!

Q

You are an androgynous figure onstage. When you choreograph, how does an awareness of that manifest in your process?

Gender, like race, is a “serious warzone.” Who is the arbiter/evaluator? When people find androgyny threatening, why must I succumb to their insecurities by making more traditional choices in dress, hairstyle, and attitude? As a woman, do you become more powerful if you emphasize your masculine side or is it that you are taken more seriously when you downplay your femininity? These questions relate to questions of power: causing confusion is, to me, a very powerful way of refocusing attention on issues far more grave than gender and/or race. I am aware that space, time, force is gendered, and in gendering these elements that make dance, I, in effect, queer the space that, hopefully, inspires dialogue.

Q

You are an androgynous figure onstage. When you choreograph, how does an awareness of that manifest in your process?

How one uses the space has a lot to do with who they are. Perhaps effort shape is one way to understand the gendered space: Clearly for me you can be muscular about time, space, force: or you can be feminine/gentle/round/ circular/measured. All the qualities one attributes to masculinity and femininity are present in use of space/time/force. A broad and perhaps exaggerated example: butoh can be a feminine (round/smooth) use of time/whereas saba, (a Senegalese traditional form,) can be a masculine (sharp/angular) use of time.

Q

How do you train today? Do you do a daily workout?

I am a runner and a serious yoga practitioner and go to the gym 6 or 7 days a week. Running leads to aerobic stamina, yoga, to strength and balance. I generally rehearse 5 days a week for a minimum of 4 hours per day. But beyond training my physical body, I am disciplined about moving towards an active integration of research and writing as part of the rigor of my artistic pursuits. Most of my dances have led me to read something new, for example, for the new work that I am currently creating, “Miriam,” the writing of Georges Didi-Huberman, on beauty. The writing I do has to do with the work at hand, for instance a script for “VISIBLE,” possible character descriptions, so perhaps you can say fictional writing that helps me see the story I am creating, literally I write the dance. This writing is absolutely private and my method, which I do not share with anyone.

Q

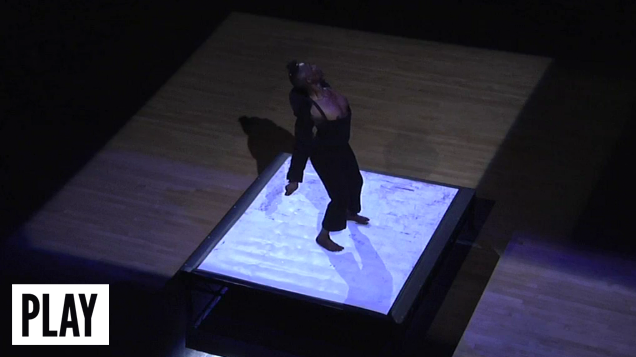

How does it feel to dance “Dark Swan?”

Very exacting, spiritually, emotionally and physically liberating. “Dark Swan” came about at a time when Darfur was huge news in western media, the displacement and murder of villagers in Sudan. Genocide was the word that was being used to describe this atrocity (following the Rwanda genocide). It seems to be rather incredible that we could all be watching another massive attack on humanity. The images of mostly fleeing women and children got me to reflect on the vulnerability of women. I also thought these women in their elegant and colorful Muslim clothes looked like swans, beautiful; and like dying swans, they seemed to be trekking to a certain death. I started to study “The Dying Swan”, the piece Michel Fokine created for Pavlova. This affecting short dance gave me a way to physicalize what I felt looking at the Darfurians in their plight.

I also looked at the work of Picasso, his “Les Demoiselles,” an astonishing portrayal of women; Dambudzo Marechera: a Zimbabwean writer‘s, “House of Hunger,” his portrayal of women long-suffering at the hands of their brothers, husbands and government institutions such as police and military (set during the Rhodesian era), as well as Degas’ portrayal of the ever young dancer. In my re-imagining of the piece, I shifted the landscape to an African desert, a sandy hot desert instead of a glacial European lake. Instead of point shoes the swan dances barefoot, in a humble tutu, bare-chested. For an African woman to dance bare-chested is both a protest and a curse of the highest order. The dance also grew from 3 minutes to 20 minutes. I recently remounted the dance on 9 men and it became a 30-minute dance. I had to lengthen the work in order to give each of the nine men a moment when to see who they were. The men were all American thus the story they could tell best was their own insecurities around the body and beauty, and less related to women, displacement etc. I learned that men are equally vulnerable about the body.

Instead of point shoes the swan dances barefoot, in a humble tutu, bare-chested. For an African woman to dance bare-chested is both a protest and a curse of the highest order. The dance also grew from 3 minutes to 20 minutes. I recently remounted the dance on 9 men and it became a 30-minute dance. I had to lengthen the work in order to give each of the nine men a moment when to could see who they were. The men were all American thus the story they could tell best was their own insecurities around the body and beauty, and less related to women, displacement etc. I learned that men are equally vulnerable about the body.

In Michael Fokine’s “The Dying Swan” we all know that the swan dies (hence the title dying swan), my “Dark Swan” defies death, resists with everything from prayer, cunning and the will to live.

Q

So in a sense you’re re-imagining not just the classic work, but also the outcome? Is the act of re-imagining an antidote?

I wanted to defy the known, why should I accept the death of the swan. Why not life instead? The “dying swan” is of its time / certain romantic conventions which Fokine was also trying to subvert. I wanted to bring a womanist point of view, a refutation of death as the only possible solution for the swan.

Q

I’d like to quote from an interview you gave in 2009: “I have questions about how one could be an individual voice in a setting where the collective is always the dominant idea. The collective starts with the family. In Africa generally, the family is very important. In the West, you find it’s the complete opposite; it’s all about the individual. I have questions about these collective systems, and how one can be independent enough to have a creative imagination…” Had you seen soloists in Zimbabwe? It sounds like you were talking, about ‘individuation,’ differentiating from the social milieu or collective, becoming “yourself.” Was becoming a solo performer a practice in which to do that?

Becoming a solo performer had to do with practical necessity: I have my body, I can work with it at all times, I am unlimited by not having space, money or other bodies. It also has to do with the fact I LIKE BEING ALONE. It has less to do with rebelling against a cultural idea (Zimbabwe, and no I had not seen any solo performers in Zimbabwe). I also think the collective is as important in the west as it is in Zimbabwe. Look at how many dance companies exist here, and teams etc. I do submit that I am intrigued by the power of the lone voice on stage. I think there is greater courage, and urgency than in a group. The lone body has nowhere to hide, the solo performer has to live and die on the strength of their presence, commitment: you are absolutely revealed. It is this vulnerability I find most fascinating, and beautiful. The communication between the solo performer and the audience is singular (like being at a museum with a Mona Lisa in front of you.) The solo voice allows for the most private and intimate of conversations. AND finally, yes, the solo affects more than my art making. The individual‘s potential is of great interest to me.

Q

Do you think that coming from Zimbabwe to work in the USA has limited the way you feel you’ve been seen?

Not entirely, as my work is contemporary. I don’t feel limited by culture/history/geography. I don’t necessarily feel limited by gender either, but I am cognizant of asserting my female identity and experience. I am aware that women’s (or my experiences) are particular because of my gender. Roles were well defined for girls and boys in my family. Without writing a dissertation on how men differ from women/ I would say I am aware that I am a woman, and there are expectations of gentility that I enjoy subverting.

Q

Is there any kind of contemporary dance scene in Zimbabwe?

Yes, the Tumbuka Dance Company.

Q

Will you be involved in Zimbabwe in the future?

I hope so: cultural ambassadorship is something I am very keen on. I plan to return to Zimbabwe next summer for the first extended stay in years. I am going to research family stories.